Two Poems by Lynn White

An Alphabetical Error

We had a map,

of course we did!

And the names of the streets

were clearly written

in English.

The names on the streets

were also clearly written

but in Cyrillic Greek,

of course they were!

This was Athens in 1966

and we were struggling

to find the Folk Museum.

Then we had a stroke of luck!

We spied a grand building

with sentries in national dress

standing outside

and we knew we’d found it!

So we went inside

and wandered around for a bit.

It was unusually empty,

the rooms and corridors devoid

of the expected folk exhibits.

A smartly dressed woman

descended the stairs

carrying a file of paper.

We asked her if she had a Guide.

She threw us out!

Of course she did!

The Royal Palace was not open to tourists!

It was to be an unrepeatable incursion.

A few months later the colonels took power

and everything changed

except the alphabet.

“An Alphabetical Error” first appeared in Pure Slush, 25 Miles From Here Anthology.

Where Are They Now?

In 1967, I hitch-hiked to Belgrade.

My friend and I would take an overnight train

to stay with our Albanian friends

in what is now Kosovo.

Until then we had some hours to kill.

The local cafe culture called

and we ate a modest meal,

two great slabs

of the ubiquitous cheese puff pastry

washed down with colas.

We went to the counter to pay

but the Server refused our money.

He pointed to a table where some guys

were enjoying a few beers.

They had already paid, he said.

We were mystified.

They had made no contact with us

and we tried to tell them we could not accept.

They explained that

they wished to thank us

for the help Britain had given in WW2.

Fast forward to 1999

when the right to self-determination was all the rage.

and NATO bombs were falling on Belgrade.

I thought about them a lot back then.

I think of them now

when territorial integrity is all the rage

and the right to self-determination

a forgotten dream.

Yes, I think of them now

when the bombs

fall in Europe

once again.

But I still have my friend in Kosovo.

Sometimes we feel human,

sometimes not.

“Where Are They Now?” first appeared in Topical Poetry.

Lynn White lives in north Wales. Her work is influenced by issues of social justice and events, places, and people she has known or imagined. She is especially interested in exploring the boundaries of dream, fantasy, and reality. She has been nominated for Pushcarts, Best of the Net, and a Rhysling Award. You can find her on her blog or on Facebook.

Two Poems by Julian Woodruff

Well on Toward December

A day almost too warm for comfort. Why

the look and sound of fall but not the feel?

The sun lies lazing in the southern sky—

veiled in tissue of cloud ordained to steal

each stretching shadow’s edge: a sight sealing a sigh.

A rustling leaf ballet inflects the light

Along lean birch limbs that will soon be bare,

yellow intensifying the bark’s white.

One branch’s last two leaves hang by a hair.

Two ancient lovers hark to every sound and sight.

Each autumn sees the story being told—

Their story—truer than the year before.

They feel themselves commingled with the gold

now drifting down, less able to ignore,

despite the warmth, the stillness of the impending cold.

The winter is their future; it will come

to them as surely as today it lies

in patience for the fall of the last plum,

claim of the snow; which underneath gray skies,

if not too late, may prove some watchful creature’s crumb.

The Plum Stump

The old plum tree was sawed off near the roots,

some branches in full leaf and others bare,

but not one promising a healthy yield—

a soon to be forgotten entity,

perhaps to be replaced eventually.

The stump looked up, a surface flat and raw,

a witness to the world of damage done,

though futile (being unattended to);

as good as dead, this remnant of the tree,

thought any who knew what it used to be.

The passing months would do the stump no favors.

The sun’s light bleached it to a ghostly pale,

and cracks appeared—the marks of heat and rain

working their weathering way with energy.

The stump slid quietly toward grotesquery.

And as decay inexorably progressed

across this surface, from the bark below

all ‘round the stump a miniature grove

of shoots sprang out, a veritable sea

of life to frustrate death’s hegemony.

Julian D. Woodruff retired from a life as an orchestral musician, teacher, and librarian (art, music). He recently moved from Rochester, NY, to Toronto, where he continues to write fiction and poetry, much of it for children. His poetry is available online at The Society of Classical Poets, Carmina, and Green Silk Journal, as well as Sparks of Calliope. WestWard Quarterly and The Lyric have also published his poetry.

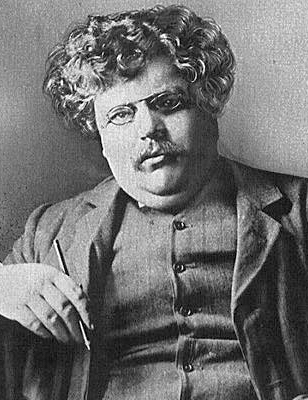

Two Poems by G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874–1936) was a prolific English writer, poet, philosopher, and critic, whose vast body of work encompassed essays, novels, plays, and over 500 poems. Known for his wit, paradoxes, and rich imagination, Chesterton’s poetry explored themes of faith, morality, beauty, and the human condition, reflecting his deep philosophical and theological convictions. His poetry was characterized by a sense of wonder, a celebration of the ordinary, and a keen understanding of the complexities of life.

Born in London, Chesterton’s literary journey began with a love of art and literature, which he studied at University College London. Although he never completed his degree, his early exposure to the visual arts influenced his poetic imagery, and his keen eye for detail became a hallmark of his work. In 1900, Chesterton published his first poetry collection, “Greybeards at Play,” a humorous and whimsical exploration of human nature that showcased his gift for clever wordplay and satirical commentary.

Chesterton’s poetry often reflected his deep religious beliefs, which became more pronounced after his conversion to Catholicism in 1922. His poem “The Ballad of the White Horse” (1911) is considered one of his masterpieces—a narrative poem that tells the story of King Alfred the Great’s battle against the invading Danes. Combining historical legend with allegory, the poem celebrated the virtues of faith, courage, and perseverance.

Many of Chesterton’s shorter poems, such as “Lepanto,” a rousing tribute to the Christian victory over the Ottoman fleet, and “A Christmas Carol,” which combined festive imagery with spiritual reflection, demonstrated his ability to weave humor, devotion, and historical insight into lyrical verse. His poetry was also marked by a profound appreciation for paradox, evident in works like “The Donkey,” where he transformed a humble, scorned animal into a symbol of divine grace.

Beyond his poetry, Chesterton’s impact on English literature was profound, with his writings influencing figures like C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien. His poetic voice remains celebrated for its clarity, joy, and intellectual depth, offering readers a window into the mind of a thinker who saw the world as a place of endless mystery and divine meaning. Today, G. K. Chesterton is remembered not only as a master of prose but also as a poet who brought wisdom and wonder to every verse he penned.

Elegy in a Country Churchyard

The men that worked for England

They have their graves at home:

And bees and birds of England

About the cross can roam.

But they that fought for England,

Following a falling star,

Alas, alas for England

They have their graves afar.

And they that rule in England,

In stately conclave met,

Alas, alas for England,

They have no graves as yet.

The Song of the Strange Ascetic

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have praised the purple vine,

My slaves should dig the vineyards,

And I would drink the wine.

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And his slaves grow lean and grey,

That he may drink some tepid milk

Exactly twice a day.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have crowned Neaera’s curls,

And filled my life with love affairs,

My house with dancing girls;

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And to lecture rooms is forced,

Where his aunts, who are not married,

Demand to be divorced.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have sent my armies forth,

And dragged behind my chariots

The Chieftains of the North.

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And he drives the dreary quill,

To lend the poor that funny cash

That makes them poorer still.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have piled my pyre on high,

And in a great red whirlwind

Gone roaring to the sky;

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And a richer man than I:

And they put him in an oven,

Just as if he were a pie.

Now who that runs can read it,

The riddle that I write,

Of why this poor old sinner,

Should sin without delight-

But I, I cannot read it

(Although I run and run),

Of them that do not have the faith,

And will not have the fun.

The informational article above was composed in part by administering guided direction to ChatGPT. It was subsequently fact-checked, revised, and edited by the editor. The editor/publisher takes no authorship credit for this work and strongly encourages disclosure when using this or similar tools to create content. Sparks of Calliope prohibits submissions of poetry composed with the assistance of predictive AI.

Two Poems by David Sapp

Fairly Certain

It’s snowing

And I am certain

Fairly certain

It will snow again

Settling lightly

Upon the orchard

Just so just so

A whirlwind of white

Unpruned branches

An exquisite chaos

Just beyond

My window for

Nearly thirty years

I have anticipated

A whirlwind of white

Blossoms each spring

But now too weary

Its limbs brittle

Dry old bones

I am certain

Fairly certain

There will be no

Flurry of petals

Only the saw

It’s heartrending

But I am certain

(Never absolutely certain)

I’ll see snow again

Blasted Oak

I am this

Blasted oak

(Well not quite yet

But soon enough)

Brittle wizened limbs

Wrenched just so

Splintered by the wind

A Friedrich painting

A poignant sublime

In stark detail

For your perusal

Far from a sapling

And now no longer

Tall stately timber

(You’d think

I’d be weary of

Ponderous allusions)

Eventually this tree

Will rot and crumble

Wend its way

Returning to loam

Nevertheless

I am this

Blasted oak

David Sapp, writer and artist, lives along the southern shore of Lake Erie in North America. A Pushcart nominee, he was awarded Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Grants for poetry and the visual arts. His poetry and prose appear widely in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. His publications include articles in the Journal of Creative Behavior, chapbooks Close to Home and Two Buddha, a novel Flying Over Erie, and a book of poems and drawingstitled Drawing Nirvana.

Two Poems by Marieta Maglas

Memories

Our love mixes with seaweed,

a sweet memory,

sprinkled with salt. It grows

between the breeze

and the hurricane,

the fruit of an inner struggle.

The green waves crash

in a murmur that

cools the warm and

ancient sand; limits; perception.

New tides of change

cast our minds back;

the courage to exist.

In the space between

ancientness and nowness,

our perfect love is eternal,

a song for a dance,

an invisible one, and

a wave-like movement

on the shores of our hearts.

We can feel our holy angels,

wounded wings,

echoes of a distant cry.

In every salty breath, a prayer

and a promise.

Between freedom and serfdom,

we fathom our dodecahedral geodesic,

spiritual sphere out.

The reality is circumjacent;

contiguous eyesight.

The voice of God becomes an echo

to inhabit the twilight world.

Echoing Shells

Bleeding shadows seemingly run away;

disappear into the blazing sand.

Wet rays hit the skin;

change the meaning

of the colors.

A new song cannot be heard;

It is not born yet.

Waves covering dead shells,

lost steps, and destroyed castles

echo with the inner silence.

Battleships are eaten imperceptibly

by the horizon.

The gales remain to scream

in the blue while bringing

ghosts to the shore.

‘Tis a new time in the old one~

always different.

Nature seems to be the same;

suffering brings peace

in an invisible way~

in this need for love.

Marieta Maglas has been published in The MockingOwl Roost, Lothlorien Journal, Verse-Virtual, Silver Birch Press, Sybaritic Press, Kingfisher Poetry, Oddville Press, Prolific Press, Dashboard Horus, Coin-Operated Press, Mayari Literature, Synchronized Chaos, Al-Khemia Poetica, PentaCat Press, The Queer Gaze, Phoenix Z Publishing, All Your Poems Magazine, Journal of the Akita International Haiku, and others. Her poems have also appeared in anthologies such as Near Kin: A Collection of Words and Art Inspired by Octavia Estelle Butler, Nancy Drew Anthology, The Cardinal Anthology Vol. 3, Ain’t no Deadbeats Around Here, and Startled by MUSIC 2023.

April is National Poetry Month

April is National Poetry Month. Started by the Academy of American Poets in 1996, this observance has not quite turned 30, yet has become an established tradition in the American poetry zeitgeist. For our part here at Sparks of Calliope, we will mark the occasion by taking another short hiatus. While I pride myself on being a man of many hats, I am absolutely swamped and a little beaten down by the present nature of public discourse. I am not giving up the mission of elevating observations of beauty and our common humanity, so we will once again return to our regular publication schedule after a brief hiatus. This means there will be no new poetry on:

April 8, 2025

April 11, 2025

April 14, 2025

April 17, 2025

April 20, 2025

April 23, 2025

April 26, 2025

April 29, 2025

Please take this opportunity to peruse past contributions to Sparks of Calliope. Present submissions will be read in the order they were received. Stay healthy, stay positive, and try not to contribute to the needless anxiety-inducing hyperbolic negativity that informs the world my children are set to inherit as they come of age.

Two Poems by Duane L Herrmann

In Just One Moment

Exploding inside me

emotions, feelings

I didn’t know existed

overwhelmed me

as I held, new

tiny human creature

I’d never seen before

and she calmed

hearing my voice,

all she needed

in that moment when

her life turned upside down,

but one point remained

and was enough.

I was lost in love

and my little life

never the same again:

I was now “Father.”

Success One

I have succeeded despite

constant failure

constant lack

absence of acceptance

all through childhood.

I’ve proved that wrong.

I am competent.

I am able

I am capable

I have achieved

and far more than those

against me.

Their efforts to restrain,

silence me,

utterly failed.

I am success!

I can carry myself

with satisfaction.

Duane L. Herrmann is an internationally published, award-winning poet and historian. His work has been translated into several languages and published in a dozen countries, in print and online. He has seven full-length collections of poetry, a sci-fi novel, a history book, and more chapbooks. His poetry has received the Robert Hayden Poetry Fellowship, inclusion in American Poets of the 1990s, Map of Kansas Literature (website), Kansas Poets Trail and others. These accomplishments defy his traumatic childhood embellished by dyslexia, ADHD, a form of mutism and, now, PTSD. He spends his time on the prairie with trees in the breeze and writes – and loves moonlight!

Two Poems by Michael Farrell

Inner Symphony

A baton raises, and it begins:

The Symphonie Fantastique,

Berlioz’ personal passion play.

Notes, only notes to me;

Much more to her.

Inside her chest- deeper than the rhythmic heart-

A hidden heart, chamber-less,

One I cannot know, may not own,

Suffused with music,

Releases itself.

I turn to watch her

As her tears break their moorings.

The young virtuoso stands rooted on the wooden stage,

Yet not there:

Lifted,

Wholly in flow,

Wholly carried, drawn by bow and string.

She is carried with him,

No-is him for a time.

I felt what he felt up there,

She says.

I was him playing the piece,

She says.

I only returned to me when he ended,

She reveals,

Says she cannot fully explain.

A rare gift, I tell her.

To live within another’s space

Even for a moment

Is the writer’s sole wish,

The artist’s dream.

On A Porch As It Rains

Lean back.

Rest,

Hands easy on the knees.

Watch this quenching curtain

Slake the earth

As the sky whispers wet,

And puddles dance specks of life.

The thrumming of drops on leaves

Calms the mind.

The body loses itself

In an indissoluble moment.

Michael Farrell was born in Bayshore, Long Island but moved to the beautiful Finger Lakes region of New York when he was four. He and his wife work from home together. He writes poetry and short fiction.

Two Translations by Rachel Lott

Translations from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Das Buch der Bilder

Maiden Melancholy

A knight, as from a proverb old,

comes riding into mind.

He came. So through the wood and wold

the storm may come and all enfold.

He passed. So evening’s benison

may pass before your prayers are done,

forsaken by the bell;

and though you’d cry aloud with woe,

you only whimper, long and low

into your kerchief cold.

A knight, as from a proverb old,

rides armored, far and fell.

His smile was fine, and softly shone

like antique light on elven-bone,

like homesickness, like Christmas snow

on darkling rooftops, like the row

of pearls set round a turquoise stone;

like soft moon-glow

upon a book loved well.

Read the original German “Mädchenmelancholie” here.

The Boy

When I grow up, I want to be like them.

They ride on wild horses through the night.

Their torches, in a trail of blazing light,

whip back like hair behind them in the wind.

I’d stand in front, as if to steer a barge,

large and like a flag I’d just unrolled,

dark, but with a helmet all of gold

alight and restless. At my back, in rank,

ten men from that same darkness in a flank,

with helmets glinting restlessly as mine,

now clear as glass, now dark and old and blind.

And one stands by me, trumpeting “make way!”

with blasts like lightning, driving all things back;

he trumpets us a loneliness so black

we speed like dreams along our rapid way.

The houses fall behind us to their knees,

beside us bow the alleys and the lanes,

we capture every place that tries to flee

and thunder on, our horses like the rains.

Read the original German “Der Knabe” here.

Rachel Lott has a background is in medieval philosophy (PhD, University of Toronto), and currently teaches Latin, logic, and English writing at private online secondary schools. In her spare time she writes and translates poetry. Her poems have appeared in First Things, the children’s magazine Cricket, and on the website of the Society of Classical Poets.