Category: Poetry Information

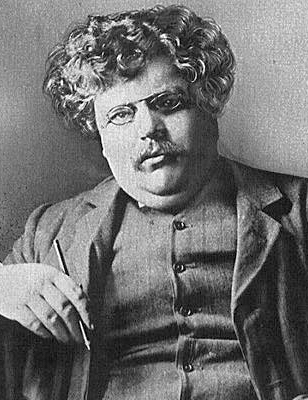

Two Poems by G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874–1936) was a prolific English writer, poet, philosopher, and critic, whose vast body of work encompassed essays, novels, plays, and over 500 poems. Known for his wit, paradoxes, and rich imagination, Chesterton’s poetry explored themes of faith, morality, beauty, and the human condition, reflecting his deep philosophical and theological convictions. His poetry was characterized by a sense of wonder, a celebration of the ordinary, and a keen understanding of the complexities of life.

Born in London, Chesterton’s literary journey began with a love of art and literature, which he studied at University College London. Although he never completed his degree, his early exposure to the visual arts influenced his poetic imagery, and his keen eye for detail became a hallmark of his work. In 1900, Chesterton published his first poetry collection, “Greybeards at Play,” a humorous and whimsical exploration of human nature that showcased his gift for clever wordplay and satirical commentary.

Chesterton’s poetry often reflected his deep religious beliefs, which became more pronounced after his conversion to Catholicism in 1922. His poem “The Ballad of the White Horse” (1911) is considered one of his masterpieces—a narrative poem that tells the story of King Alfred the Great’s battle against the invading Danes. Combining historical legend with allegory, the poem celebrated the virtues of faith, courage, and perseverance.

Many of Chesterton’s shorter poems, such as “Lepanto,” a rousing tribute to the Christian victory over the Ottoman fleet, and “A Christmas Carol,” which combined festive imagery with spiritual reflection, demonstrated his ability to weave humor, devotion, and historical insight into lyrical verse. His poetry was also marked by a profound appreciation for paradox, evident in works like “The Donkey,” where he transformed a humble, scorned animal into a symbol of divine grace.

Beyond his poetry, Chesterton’s impact on English literature was profound, with his writings influencing figures like C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien. His poetic voice remains celebrated for its clarity, joy, and intellectual depth, offering readers a window into the mind of a thinker who saw the world as a place of endless mystery and divine meaning. Today, G. K. Chesterton is remembered not only as a master of prose but also as a poet who brought wisdom and wonder to every verse he penned.

Elegy in a Country Churchyard

The men that worked for England

They have their graves at home:

And bees and birds of England

About the cross can roam.

But they that fought for England,

Following a falling star,

Alas, alas for England

They have their graves afar.

And they that rule in England,

In stately conclave met,

Alas, alas for England,

They have no graves as yet.

The Song of the Strange Ascetic

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have praised the purple vine,

My slaves should dig the vineyards,

And I would drink the wine.

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And his slaves grow lean and grey,

That he may drink some tepid milk

Exactly twice a day.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have crowned Neaera’s curls,

And filled my life with love affairs,

My house with dancing girls;

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And to lecture rooms is forced,

Where his aunts, who are not married,

Demand to be divorced.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have sent my armies forth,

And dragged behind my chariots

The Chieftains of the North.

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And he drives the dreary quill,

To lend the poor that funny cash

That makes them poorer still.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have piled my pyre on high,

And in a great red whirlwind

Gone roaring to the sky;

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And a richer man than I:

And they put him in an oven,

Just as if he were a pie.

Now who that runs can read it,

The riddle that I write,

Of why this poor old sinner,

Should sin without delight-

But I, I cannot read it

(Although I run and run),

Of them that do not have the faith,

And will not have the fun.

The informational article above was composed in part by administering guided direction to ChatGPT. It was subsequently fact-checked, revised, and edited by the editor. The editor/publisher takes no authorship credit for this work and strongly encourages disclosure when using this or similar tools to create content. Sparks of Calliope prohibits submissions of poetry composed with the assistance of predictive AI.

April is National Poetry Month

April is National Poetry Month. Started by the Academy of American Poets in 1996, this observance has not quite turned 30, yet has become an established tradition in the American poetry zeitgeist. For our part here at Sparks of Calliope, we will mark the occasion by taking another short hiatus. While I pride myself on being a man of many hats, I am absolutely swamped and a little beaten down by the present nature of public discourse. I am not giving up the mission of elevating observations of beauty and our common humanity, so we will once again return to our regular publication schedule after a brief hiatus. This means there will be no new poetry on:

April 8, 2025

April 11, 2025

April 14, 2025

April 17, 2025

April 20, 2025

April 23, 2025

April 26, 2025

April 29, 2025

Please take this opportunity to peruse past contributions to Sparks of Calliope. Present submissions will be read in the order they were received. Stay healthy, stay positive, and try not to contribute to the needless anxiety-inducing hyperbolic negativity that informs the world my children are set to inherit as they come of age.

Two Poems by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) was a leading English Romantic poet, critic, and philosopher, best known for his imaginative verse and profound influence on literary theory. A central figure in the Romantic movement, Coleridge’s work is celebrated for its rich symbolism, vivid imagery, and exploration of the supernatural. Alongside his close friend William Wordsworth, he helped revolutionize English poetry with the publication of Lyrical Ballads (1798), a collection that marked the dawn of Romanticism.

Born in Ottery St Mary, Devon, Coleridge was the son of a clergyman and displayed prodigious intellect from an early age. He attended Christ’s Hospital School in London, where he formed a deep appreciation for literature, and later studied at Jesus College, Cambridge. However, financial struggles and personal turmoil led him to abandon his degree. During this period, he became interested in radical politics and utopian ideas, even briefly planning a communal society, or “Pantisocracy,” in America with fellow poet Robert Southey. Though this dream never materialized, it reflected his lifelong fascination with idealism and social reform.

Coleridge’s poetic genius is most evident in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Kubla Khan, two of his most famous works. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner is a haunting narrative poem filled with supernatural elements, moral ambiguity, and vivid natural imagery, while Kubla Khan, written under the influence of an opium-induced dream, captures an ethereal vision of creativity and lost splendor. His poetry often explores themes of nature, imagination, and the sublime, hallmarks of Romantic thought.

Despite his literary achievements, Coleridge struggled with ill health, financial instability, and a debilitating addiction to opium, which deeply affected his personal and professional life. His philosophical and critical writings, including Biographia Literaria (1817), had a profound impact on literary theory, introducing concepts of imagination and organic form that influenced generations of writers and thinkers.

In his later years, Coleridge withdrew from public life, living under the care of friends while continuing to write on philosophy, theology, and metaphysics. Though overshadowed in his lifetime by Wordsworth, his reputation grew after his death, and he is now regarded as one of the most original and influential minds of the Romantic era. His poetry and critical thought continue to shape literary studies, ensuring his legacy as a visionary poet and intellectual.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge is suggested quite often by readers as a poet who belongs on our list of the 5 Best Classic English Poets. And, while “Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner” is often sited as Coleridge’s best work, shorter poems that showcase his talent include “Frost at Midnight” and “Kubla Khan.” These can be read below.

Frost at Midnight

The Frost performs its secret ministry,

Unhelped by any wind. The owlet’s cry

Came loud—and hark, again! loud as before.

The inmates of my cottage, all at rest,

Have left me to that solitude, which suits

Abstruser musings: save that at my side

My cradled infant slumbers peacefully.

‘Tis calm indeed! so calm, that it disturbs

And vexes meditation with its strange

And extreme silentness. Sea, hill, and wood,

This populous village! Sea, and hill, and wood,

With all the numberless goings-on of life,

Inaudible as dreams! the thin blue flame

Lies on my low-burnt fire, and quivers not;

Only that film, which fluttered on the grate,

Still flutters there, the sole unquiet thing.

Methinks, its motion in this hush of nature

Gives it dim sympathies with me who live,

Making it a companionable form,

Whose puny flaps and freaks the idling Spirit

By its own moods interprets, every where

Echo or mirror seeking of itself,

And makes a toy of Thought.

But O! how oft,

How oft, at school, with most believing mind,

Presageful, have I gazed upon the bars,

To watch that fluttering stranger ! and as oft

With unclosed lids, already had I dreamt

Of my sweet birth-place, and the old church-tower,

Whose bells, the poor man’s only music, rang

From morn to evening, all the hot Fair-day,

So sweetly, that they stirred and haunted me

With a wild pleasure, falling on mine ear

Most like articulate sounds of things to come!

So gazed I, till the soothing things, I dreamt,

Lulled me to sleep, and sleep prolonged my dreams!

And so I brooded all the following morn,

Awed by the stern preceptor’s face, mine eye

Fixed with mock study on my swimming book:

Save if the door half opened, and I snatched

A hasty glance, and still my heart leaped up,

For still I hoped to see the stranger’s face,

Townsman, or aunt, or sister more beloved,

My play-mate when we both were clothed alike!

Dear Babe, that sleepest cradled by my side,

Whose gentle breathings, heard in this deep calm,

Fill up the intersperséd vacancies

And momentary pauses of the thought!

My babe so beautiful! it thrills my heart

With tender gladness, thus to look at thee,

And think that thou shalt learn far other lore,

And in far other scenes! For I was reared

In the great city, pent ‘mid cloisters dim,

And saw nought lovely but the sky and stars.

But thou, my babe! shalt wander like a breeze

By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags

Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds,

Which image in their bulk both lakes and shores

And mountain crags: so shalt thou see and hear

The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible

Of that eternal language, which thy God

Utters, who from eternity doth teach

Himself in all, and all things in himself.

Great universal Teacher! he shall mould

Thy spirit, and by giving make it ask.

Therefore all seasons shall be sweet to thee,

Whether the summer clothe the general earth

With greenness, or the redbreast sit and sing

Betwixt the tufts of snow on the bare branch

Of mossy apple-tree, while the nigh thatch

Smokes in the sun-thaw; whether the eave-drops fall

Heard only in the trances of the blast,

Or if the secret ministry of frost

Shall hang them up in silent icicles,

Quietly shining to the quiet Moon.

Kubla Khan

Or, a vision in a dream. A Fragment.

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round;

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething,

As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing,

A mighty fountain momently was forced:

Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst

Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail,

Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail:

And mid these dancing rocks at once and ever

It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean;

And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war!

The shadow of the dome of pleasure

Floated midway on the waves;

Where was heard the mingled measure

From the fountain and the caves.

It was a miracle of rare device,

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw:

It was an Abyssinian maid

And on her dulcimer she played,

Singing of Mount Abora.

Could I revive within me

Her symphony and song,

To such a deep delight ’twould win me,

That with music loud and long,

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

The informational article above was composed in part by administering guided direction to ChatGPT. It was subsequently fact-checked, revised, and edited by the editor. The editor/publisher takes no authorship credit for this work and strongly encourages disclosure when using this or similar tools to create content. Sparks of Calliope prohibits submissions of poetry composed with the assistance of predictive AI.

Happy Holidays!

Sparks of Calliope hopes you have a safe and enjoyable holiday season. We are taking a short hiatus. There will be no poems published on:

December 21, 2024

December 24, 2024

December 27, 2024

December 30, 2024

January 2, 2024

January 5, 2024

Thank you for your continued interest in Sparks of Calliope.

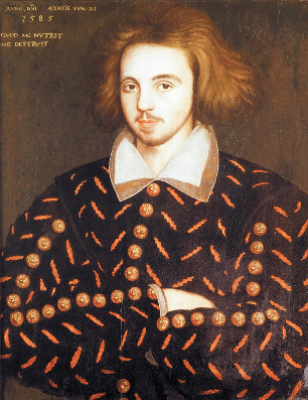

Two Poems by Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593) remains a towering figure of the English Renaissance, celebrated for his profound influence on Elizabethan drama and poetry. Born in Canterbury, the son of a shoemaker, Marlowe attended the King’s School and later Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where he excelled in classical studies and earned a reputation for his brilliance and unorthodox thinking. His education, likely subsidized by influential patrons, provided him with the foundation for his later works that would redefine the English stage.

A contemporary of William Shakespeare, Marlowe is often credited with elevating the theatrical art form through his use of blank verse and grandiose themes. His plays, marked by their intellectual depth, bold exploration of power, and complex characters, include masterpieces such as Tamburlaine the Great, Doctor Faustus, and The Jew of Malta. These works delve into themes of ambition, morality, and human striving, reflecting Marlowe’s fascination with the limits of human potential and the price of overreaching.

Marlowe’s most famous play, Doctor Faustus, tells the story of a man who sells his soul to the devil in exchange for knowledge and power, a narrative that mirrors the playwright’s own interest in challenging societal and theological norms. His lyrical poetry, such as the pastoral elegy The Passionate Shepherd to His Love, showcases his ability to craft both profound and delicate verse, securing his place among the great poets of his age.

Despite his artistic achievements, Marlowe’s life was as dramatic and enigmatic as his works. A suspected spy for Queen Elizabeth’s government, he operated in shadowy political circles, which may have contributed to his mysterious death. In 1593, at just 29 years old, Marlowe was fatally stabbed in what was officially deemed a dispute over a debt, though speculation persists regarding political intrigue or espionage.

Marlowe’s untimely death robbed the world of a playwright whose genius might have rivaled or surpassed Shakespeare’s. Nevertheless, his influence endures, particularly in the development of blank verse and the portrayal of ambitious, larger-than-life characters. Marlowe’s legacy lies in his fearless exploration of human desire and defiance, his works offering a daring and innovative vision that continues to resonate with audiences and readers, cementing his status as a cornerstone of English literature.

Marlowe’s most recognizable poem (found below) would be “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love,” which was famous enough for Sir Walter Raleigh to write a response a few years later. Another notable work was the unfinished “Hero and Leander,” a lengthy poem which is also exerpted below.

The Passionate Shepherd to His Love

Come live with me and be my love,

And we will all the pleasures prove,

That Valleys, groves, hills, and fields,

Woods, or steepy mountain yields.

And we will sit upon the Rocks,

Seeing the Shepherds feed their flocks,

By shallow Rivers to whose falls

Melodious birds sing Madrigals.

And I will make thee beds of Roses

And a thousand fragrant posies,

A cap of flowers, and a kirtle

Embroidered all with leaves of Myrtle;

A gown made of the finest wool

Which from our pretty Lambs we pull;

Fair lined slippers for the cold,

With buckles of the purest gold;

A belt of straw and Ivy buds,

With Coral clasps and Amber studs:

And if these pleasures may thee move,

Come live with me, and be my love.

The Shepherds’ Swains shall dance and sing

For thy delight each May-morning:

If these delights thy mind may move,

Then live with me, and be my love.

It lies not in our power to love or hate

an excerpt from “Hero and Leander“

It lies not in our power to love or hate,

For will in us is overruled by fate.

When two are stripped, long ere the course begin,

We wish that one should lose, the other win;

And one especially do we affect

Of two gold ingots, like in each respect:

The reason no man knows; let it suffice

What we behold is censured by our eyes.

Where both deliberate, the love is slight:

Who ever loved, that loved not at first sight?

The informational article above was composed in part by administering guided direction to ChatGPT. It was subsequently fact-checked, revised, and edited by the editor. The editor/publisher takes no authorship credit for this work and strongly encourages disclosure when using this or similar tools to create content. Sparks of Calliope prohibits submissions of poetry composed with the assistance of predictive AI.

Two Poems by James Joyce

James Joyce (1882–1941) stands as one of the most celebrated and revolutionary figures in modern literature. Born into a middle-class family in Rathgar, Dublin, Joyce grew up in a rapidly changing Ireland, a backdrop that would profoundly shape his literary imagination. Educated by the Jesuits at Clongowes Wood College and later at University College Dublin, he excelled in languages and literature, developing a fascination with philosophy, aesthetics, and the complexities of human experience.

A writer of unparalleled innovation, Joyce’s works are known for their intricate use of language, stream-of-consciousness techniques, and deep psychological insight. His early collection, Dubliners (1914), presents a vivid portrait of Dublin life, marked by themes of paralysis and epiphany. His groundbreaking novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) introduced his semi-autobiographical protagonist Stephen Dedalus, exploring themes of identity, rebellion, and artistic freedom.

Joyce’s magnum opus, Ulysses (1922), reimagines Homer’s Odyssey in the streets of Dublin over a single day, June 16, 1904. This modernist masterpiece employs experimental techniques, rich allusions, and meticulous detail, capturing the inner lives of its characters and elevating the mundane to the mythic. Though initially controversial and banned in several countries for its explicit content, Ulysses solidified Joyce’s reputation as a literary pioneer.

Joyce’s commitment to his craft often came at personal and financial cost. His self-imposed exile from Ireland took him to cities like Trieste, Zurich, and Paris, where he struggled with poverty and deteriorating eyesight while devoting himself to his art. His final work, Finnegans Wake (1939), pushed the boundaries of language and narrative further, presenting a dreamlike, cyclical exploration of history, myth, and the unconscious.

Joyce’s relationship with Ireland was both loving and contentious. While his works immortalize Dublin and its inhabitants, his criticism of Irish nationalism and religion often alienated him from his contemporaries. Yet, he remains a towering figure in Irish literature, capturing the essence of his homeland with unparalleled depth and complexity.

Despite his avant-garde style, Joyce’s themes of love, loss, identity, and human connection resonate universally. His legacy as a literary innovator continues to inspire writers and scholars worldwide, affirming his place as a cornerstone of modernist literature. “The Twilight Turns” and “At That Hour,” both found below, are two of his better known poems.

The Twilight Turns

The twilight turns from amethyst

To deep and deeper blue,

The lamp fills with a pale green glow

The trees of the avenue.

The old piano plays an air,

Sedate and slow and gay;

She bends upon the yellow keys,

Her head inclines this way.

Shy thought and grave wide eyes and hands

That wander as they list — –

The twilight turns to darker blue

With lights of amethyst.

At That Hour

At that hour when all things have repose,

O lonely watcher of the skies,

Do you hear the night wind and the sighs

Of harps playing unto Love to unclose

The pale gates of sunrise?

When all things repose, do you alone

Awake to hear the sweet harps play

To Love before him on his way,

And the night wind answering in antiphon

Till night is overgone?

Play on, invisible harps, unto Love,

Whose way in heaven is aglow

At that hour when soft lights come and go,

Soft sweet music in the air above

And in the earth below.

The informational article above was composed in part by administering guided direction to ChatGPT. It was subsequently fact-checked, revised, and edited by the editor. The editor/publisher takes no authorship credit for this work and strongly encourages disclosure when using this or similar tools to create content. Sparks of Calliope prohibits submissions of poetry composed with the assistance of predictive AI.

We’ll Be Right Back!

Sparks of Calliope is taking a brief intermission. We will return on December 6, 2024. There will be no poems published for:

November 27, 2024

November 30, 2024

December 3, 2024

Thank you for coming to see us!

5 Best Classic English Poets

Here at Sparks of Calliope, we define “classic” poets as poets who are widely read, have been studied academically, and whose work is in the public domain. Classic is commonly defined as “a body of work of recognized and established value.” This is not to be confused with the other definition of classic as involving the study of Ancient Greek and Latin literature. Here is a quick list of the top 5 British classic poets with links to biographies and a couple of samples from each. We would love to get your take on this order in the comments!

- William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

Undoubtedly the most famous poet of all time in the English-speaking world, William Shakespeare’s works are still being reproduced, adapted, and referenced in popular culture more than 400 years after his death. His famous plays overshadow his poetry, but do not detract from his recognition as a skillful poet in his own right. His literary influence on Western Civilization can hardly be overstated. We chose to feature “Sonnet 116” and “Sonnet 18” as two of his most popular poems.

2. George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (1788-1824)

Lord Byron was the English version of Giacomo Casanova. Most famous for his lengthy poem entitled “Don Juan,” we chose “She Walks in Beauty” and “And Thou Art Dead, as Young and Fair” to represent the best of his work. Despite his current place of esteem in the hearts of his countrymen, his unpopularity with certain portions of the population during his lifetime led him to self-exile, and he died from illness while fighting the Turks in the Greek War of Independence.

3. John Keats (1795-1821)

Admired for literary works of profound depth despite his young age and short time on this earth, John Keats is the poster child for the Romantic movement. We chose “Ode to a Nightingale” and “Ode to a Grecian Urn” to demonstrate his emotional depth and skillful use of imagery. While his life was cut short due to tuberculosis–he died at the age of 25–he nevertheless managed to write works which continue to inspire and earn him a place among the top five British poets of all time.

4. Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

Described by one modern critic as “a lyric poet without rival,” Percy Shelley’s place as one of the best all-time classic British poets is not undisputed. Both T. S. Elliot and W. H. Auden are on record as fierce critics of his work. The notorious historical figure Karl Marx, on the other hand, was said to be an admirer. An atheist and political activist, Percy Shelley did not live to see much of his work published. However, the quality of his work earns him a place on our list. We chose “Ozymandias” and “To a Skylark” to showcase his talent.

5. John Milton (1608-1674)

His most famous work, Paradise Lost, is so lengthy that seldom appears in samplings such as this; however, John Milton wrote shorter poems that are worthy examples of his abilities. He wrote his poems from a position of deeply-held religious beliefs and with a highly educated background. His works are highly intellectual if not profoundly philosophical, exploring themes such as divine justice and individual liberty along with other aspects of human existence. We decided upon “An Epitaph on the Admirable Dramatic Poet W. Shakespeare” and “On His Blindness” to highlight his writing ability.

Did we get our order right? What would yours be instead? How would you round out the top 10? We look forward to reading your comments!

Two Poems by Richard Lovelace

Richard Lovelace (1617–1657) was a prominent Cavalier poet of the 17th century, renowned for his lyrical elegance and association with the Royalist cause during the English Civil War. Born into a well-to-do Kentish family, Lovelace was educated at the prestigious Charterhouse School and later at Gloucester Hall, Oxford, where his charm, good looks, and poetic skill quickly gained him admiration and support among the literary elite. Known for his refined manners and loyalty to King Charles I, Lovelace’s life and work were deeply influenced by his unwavering commitment to the Royalist ideals of honor, loyalty, and courtly love.

Lovelace’s poetry is marked by its musical quality, emotive depth, and dedication to the ideals of chivalry. His most famous work, To Althea, from Prison, penned while he was briefly imprisoned for his Royalist sympathies, contains the immortal lines, “Stone walls do not a prison make, / Nor iron bars a cage.” This piece and others in his collection Lucasta (1649) express his belief in inner freedom and resilience, as well as his love for a woman he called Lucasta (thought to be a poetic pseudonym for his beloved Lucy Sacheverell). Lovelace’s verses often celebrate themes of loyalty, love, and liberty, reflecting his desire for both personal and political freedom during a time of national turmoil.

Lovelace’s commitment to the Royalist cause led him to serve in the military on behalf of King Charles I, fighting in the Bishops’ Wars in Scotland and later in the Civil War. However, his loyalty came at great personal cost. After repeated imprisonments and financial losses, he spent his later years in poverty and ill health, facing the bitter disillusionment that many Cavaliers experienced after the fall of the monarchy.

Lovelace’s legacy as a poet rests on his ability to merge graceful language with Cavalier ideals. His verses capture the spirit of a turbulent era, and his enduring works offer insight into the personal sacrifices of those loyal to a lost cause. Though his fame dwindled after his death, Lovelace’s poetry was rediscovered in the 19th century, appreciated for its lyrical beauty and its emblematic portrayal of honor and love. His work, including the two poems featured below, remains a touchstone of the Cavalier tradition, influencing later poets and reminding readers of the values of courage, loyalty, and resilience.

To Althea, From Prison

When Love with unconfinèd wings

Hovers within my Gates,

And my divine Althea brings

To whisper at the Grates;

When I lie tangled in her hair,

And fettered to her eye,

The Gods that wanton in the Air,

Know no such Liberty.

When flowing Cups run swiftly round

With no allaying Thames,

Our careless heads with Roses bound,

Our hearts with Loyal Flames;

When thirsty grief in Wine we steep,

When Healths and draughts go free,

Fishes that tipple in the Deep

Know no such Liberty.

When (like committed linnets) I

With shriller throat shall sing

The sweetness, Mercy, Majesty,

And glories of my King;

When I shall voice aloud how good

He is, how Great should be,

Enlargèd Winds, that curl the Flood,

Know no such Liberty.

Stone Walls do not a Prison make,

Nor Iron bars a Cage;

Minds innocent and quiet take

That for an Hermitage.

If I have freedom in my Love,

And in my soul am free,

Angels alone that soar above,

Enjoy such Liberty.

To Lucasta, Going to the Wars

Tell me not (Sweet) I am unkind,

That from the nunnery

Of thy chaste breast and quiet mind

To war and arms I fly.

True, a new mistress now I chase,

The first foe in the field;

And with a stronger faith embrace

A sword, a horse, a shield.

Yet this inconstancy is such

As you too shall adore;

I could not love thee (Dear) so much,

Lov’d I not Honour more.