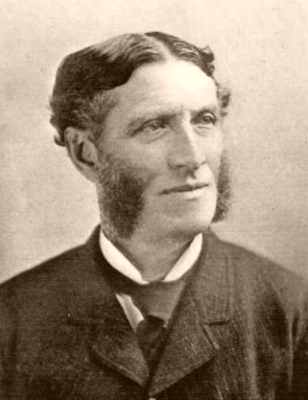

Wilfred Owen (1893–1918) was a British poet whose powerful works provide some of the most poignant insights into the horrors of World War I. Born in Oswestry, Shropshire, England, Owen grew up in a lower-middle-class family. His early education sparked an interest in poetry, and he was influenced by Romantic poets such as John Keats. However, it was his experiences as a soldier during World War I that would most profoundly shape his poetic voice and themes.

Owen enlisted in the British Army in 1915, at the age of 22. He was initially enthusiastic about joining the war effort, driven by a sense of duty and patriotism. His perspectives, however, drastically shifted after witnessing the brutal realities of trench warfare. In 1917, he suffered from shell shock (now known as post-traumatic stress disorder) and was sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh, where he met fellow poet Siegfried Sassoon. This meeting proved crucial, as Sassoon became a mentor and friend, encouraging Owen to channel his experiences of war into his poetry.

Owen’s poems, written during the last two years of his life, are marked by their vivid imagery and intense emotional force. In stark contrast to romanticized portrayals of war, his poems expose war’s brutality and the suffering of soldiers. Works such as “Dulce et Decorum Est” and “Anthem for Doomed Youth” found below are renowned for their bold depictions of the physical and psychological trauma experienced by combatants. His use of half-rhyme, vivid descriptions, and shocking realism set his work apart from other war poetry of the time.

Tragically, Owen was killed in action on November 4, 1918, just one week before the Armistice that ended World War I. His death cut short a promising literary career, but his legacy endures through his powerful poetry, which continues to resonate with readers. Published posthumously, his work has become some of the most significant literary accounts of World War I, forever altering the perception of war in English literature.

Dulce et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Anthem for Doomed Youth

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

— Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,—

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls' brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.