After four years of posting almost every three days (or about 121 posts per year), Sparks of Calliope is taking a month-long hiatus to rest, recoup, and regroup. All unread submissions past and present will be considered in the order they were received. Our next scheduled poetry will post on July 21, 2023. In the meantime, we encourage you to browse our past contributors, like and comment on their work, and maybe even donate to help keep this endeavor afloat if you find us worthy. We’ll be right back, bringing you the quality poetry you have come to expect from our journal. Thank you for visiting!

Category: Poetry Information

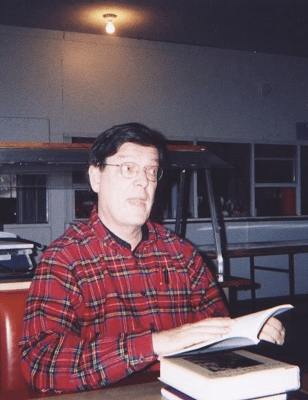

Dr. W. Nicholas Knight (April 18, 1939 – October 23, 2022)

It would seem unfitting to me not to mention Dr. W. Nicholas Knight–who died this past year–when educating others about William Shakespeare. His obituary explains:

“Nick was a popular professor of English, first at Indiana University Bloomington, then Wesleyan University in Connecticut, and lastly Missouri University of Science and Technology, previously the University of Missouri – Rolla. He earned his B.A. in English from Amherst College, M.A. from the University of California at Berkeley, and Ph.D. from Indiana University. He knew his students well, encouraging them in their endeavors and writing. Three of the known signatures of William Shakespeare were discovered or authenticated by Nick. Professor Knight rendered college more accessible by teaching community college courses at night, sponsoring the Black Student Union, taking senior citizens on field trips to St. Louis, teaching Shakespeare in prison, and mentoring English majors whose parents thought they should major in engineering. Nick Knight’s representative works include his book Shakespeare’s Hidden Life and his off-Broadway play “The Death of J.K.” He was active in Arts Rolla, Rotary Club, and the National Endowment for the Humanities.”

My whole conceptualization of who I was to become professionally was first modeled after this man. He was my favorite professor, my advisor, my mentor, and my friend. I was witness not only to Dr. Knight’s knowledgeable passion for all things Shakespeare but also to his passion for Civil War miniature soldiers, model trains, and the fascinating historical knowledge these things represented. Whether he was retelling his story of almost running over Robert Frost with his car at Amherst, giddily boasting of the number of U.S. Poet Laureates he had driven around in his car, or showing off the blurb John Updike had written for his Arthurian poetry collection, he made the undergraduate experience of this literature lover nothing short of magical.

(I was also reminded by former classmates of his story of personal friendship with Superman actor Christopher Reeve, and how the character of Clark Kent in those movies was supposedly modeled after Dr. Knight. The resemblance and mannerisms are uncanny…).

“The New Colossus” by Emma Lazarus

Emma Lazarus (1849-1887), although a prolific writer for such a short life of 38 years, is best known for her sonnet, “The New Colossus,” some lines of which are inscribed on a bronze plaque which was installed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty in 1903. While this poem wasn’t widely known in her lifetime, she was a recognized literary figure who was acquainted with many literary and political figures of the day. Ironically, “The New Colossus” later became so famous that it overshadowed her legacy as a whole. Read more about Emma Lazarus here.

The New Colossus

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

‘Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!’ cries she

With silent lips. ‘Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!’

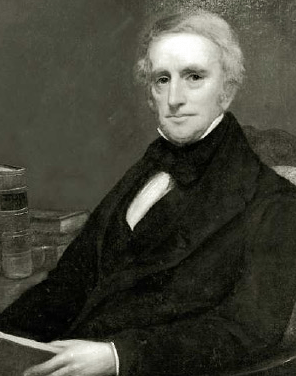

“A Visit from St. Nicholas” by Clement Clark Moore

Clement Clark Moore (1779-1863) was a poet and academic who is best remembered for the following poem which he claimed to have written for his children. Although he was acknowledged throughout his lifetime as the undisputed author of the poem, which was originally published anonymously in 1823, some modern scholars have suggested a different author actually wrote the poem. What is indisputable is that the poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” is one of the most well-known poems ever written by an American poet, and has been singularly responsible for many current conceptions of Santa Claus and Christmas gift-giving in secular American culture.

Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there;

The children were nestled all snug in their beds;

While visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads;

And mamma in her ‘kerchief, and I in my cap,

Had just settled our brains for a long winter’s nap,

When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter,

I sprang from my bed to see what was the matter.

Away to the window I flew like a flash,

Tore open the shutters and threw up the sash.

The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow,

Gave a lustre of midday to objects below,

When what to my wondering eyes did appear,

But a miniature sleigh and eight tiny rein-deer,

With a little old driver so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment he must be St. Nick.

More rapid than eagles his coursers they came,

And he whistled, and shouted, and called them by name:

“Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now Prancer and Vixen!

On, Comet! on, Cupid! on, Donner and Blitzen!

To the top of the porch! to the top of the wall!

Now dash away! dash away! dash away all!”

As leaves that before the wild hurricane fly,

When they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky;

So up to the housetop the coursers they flew

With the sleigh full of toys, and St. Nicholas too—

And then, in a twinkling, I heard on the roof

The prancing and pawing of each little hoof.

As I drew in my head, and was turning around,

Down the chimney St. Nicholas came with a bound.

He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot,

And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot;

A bundle of toys he had flung on his back,

And he looked like a peddler just opening his pack.

His eyes—how they twinkled! his dimples, how merry!

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry!

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow,

And the beard on his chin was as white as the snow;

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke, it encircled his head like a wreath;

He had a broad face and a little round belly

That shook when he laughed, like a bowl full of jelly.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf,

And I laughed when I saw him, in spite of myself;

A wink of his eye and a twist of his head

Soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread;

He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work,

And filled all the stockings; then turned with a jerk,

And laying his finger aside of his nose,

And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose;

He sprang to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle,

And away they all flew like the down of a thistle.

But I heard him exclaim, ere he drove out of sight—

“Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good night!”