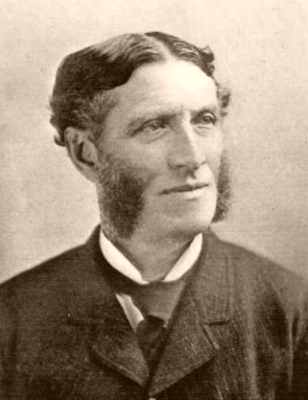

Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) was a prominent English poet, cultural critic, and educator who made significant contributions to Victorian literature and thought. Born into an intellectually distinguished family, Arnold was the son of the renowned headmaster Thomas Arnold of Rugby School, which deeply influenced his perspectives on education and culture.

Arnold’s poetry is often characterized by its reflection on the spiritual and emotional challenges of the modern age, as well as its exploration of human isolation and the loss of faith in an increasingly industrialized and secular world. His most famous poem, “Dover Beach,” epitomizes these themes, portraying a world where the “Sea of Faith” has retreated, leaving humanity exposed to the harsh realities of existence. The melancholy tone and contemplative style of Arnold’s poetry have cemented his place as a leading figure of Victorian poetry, bridging the gap between Romanticism and Modernism.

In addition to his poetry, Arnold was a formidable critic and essayist, particularly known for his works on cultural and literary criticism. His collection of essays, Culture and Anarchy (1869), remains one of his most influential works. In it, Arnold argued for the importance of “culture”—which he defined as the pursuit of perfection through knowledge and appreciation of the arts—as a means of countering the anarchy of industrial society. He believed that culture could act as a unifying force, bringing together different social classes and fostering moral and intellectual improvement.

Arnold’s work as an inspector of schools for over three decades also had a lasting impact on English education. His reports and writings on education emphasized the need for broad access to quality education and the importance of fostering a well-rounded, humane curriculum.

Though his poetry often reflects a sense of loss and disillusionment, Arnold’s commitment to cultural and educational ideals demonstrates his belief in the possibility of human improvement and the power of intellectual and moral development. His contributions to both literature and cultural criticism have left a lasting legacy, influencing not only his contemporaries but also future generations of writers and thinkers.

“Dover Beach” and “The Buried Life” are a couple of his better known poems:

Dover Beach

The sea is calm tonight.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Ægean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

The Buried Life

Light flows our war of mocking words, and yet,

Behold, with tears mine eyes are wet!

I feel a nameless sadness o’er me roll.

Yes, yes, we know that we can jest,

We know, we know that we can smile!

But there’s a something in this breast,

To which thy light words bring no rest,

And thy gay smiles no anodyne.

Give me thy hand, and hush awhile,

And turn those limpid eyes on mine,

And let me read there, love! thy inmost soul.

Alas! is even love too weak

To unlock the heart, and let it speak?

Are even lovers powerless to reveal

To one another what indeed they feel?

I knew the mass of men conceal’d

Their thoughts, for fear that if reveal’d

They would by other men be met

With blank indifference, or with blame reproved;

I knew they lived and moved

Trick’d in disguises, alien to the rest

Of men, and alien to themselves—and yet

The same heart beats in every human breast!

But we, my love!—doth a like spell benumb

Our hearts, our voices?—must we too be dumb?

Ah! well for us, if even we,

Even for a moment, can get free

Our heart, and have our lips unchain’d;

For that which seals them hath been deep-ordain’d!

Fate, which foresaw

How frivolous a baby man would be—

By what distractions he would be possess’d,

How he would pour himself in every strife,

And well-nigh change his own identity—

That it might keep from his capricious play

His genuine self, and force him to obey

Even in his own despite his being’s law,

Bade through the deep recesses of our breast

The unregarded river of our life

Pursue with indiscernible flow its way;

And that we should not see

The buried stream, and seem to be

Eddying at large in blind uncertainty,

Though driving on with it eternally.

But often, in the world’s most crowded streets,

But often, in the din of strife,

There rises an unspeakable desire

After the knowledge of our buried life;

A thirst to spend our fire and restless force

In tracking out our true, original course;

A longing to inquire

Into the mystery of this heart which beats

So wild, so deep in us—to know

Whence our lives come and where they go.

And many a man in his own breast then delves,

But deep enough, alas! none ever mines.

And we have been on many thousand lines,

And we have shown, on each, spirit and power;

But hardly have we, for one little hour,

Been on our own line, have we been ourselves—

Hardly had skill to utter one of all

The nameless feelings that course through our breast,

But they course on for ever unexpress’d.

And long we try in vain to speak and act

Our hidden self, and what we say and do

Is eloquent, is well—but ‘t is not true!

And then we will no more be rack’d

With inward striving, and demand

Of all the thousand nothings of the hour

Their stupefying power;

Ah yes, and they benumb us at our call!

Yet still, from time to time, vague and forlorn,

From the soul’s subterranean depth upborne

As from an infinitely distant land,

Come airs, and floating echoes, and convey

A melancholy into all our day.

Only—but this is rare—

When a belovèd hand is laid in ours,

When, jaded with the rush and glare

Of the interminable hours,

Our eyes can in another’s eyes read clear,

When our world-deafen’d ear

Is by the tones of a loved voice caress’d—

A bolt is shot back somewhere in our breast,

And a lost pulse of feeling stirs again.

The eye sinks inward, and the heart lies plain,

And what we mean, we say, and what we would, we know.

A man becomes aware of his life’s flow,

And hears its winding murmur; and he sees

The meadows where it glides, the sun, the breeze.

And there arrives a lull in the hot race

Wherein he doth for ever chase

That flying and elusive shadow, rest.

An air of coolness plays upon his face,

And an unwonted calm pervades his breast.

And then he thinks he knows

The hills where his life rose,

And the sea where it goes.

The informational article above was composed in part by administering guided direction to ChatGPT. It was subsequently fact-checked, revised, and edited by the editor. The editor/publisher takes no authorship credit for this work and strongly encourages disclosure when using this or similar tools to create content. Sparks of Calliope prohibits submissions of poetry composed with the assistance of predictive AI.