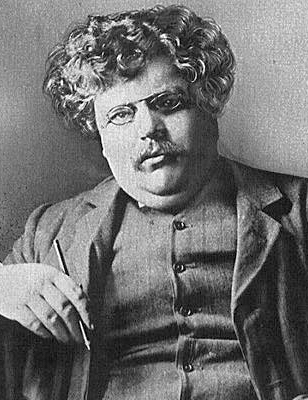

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874–1936) was a prolific English writer, poet, philosopher, and critic, whose vast body of work encompassed essays, novels, plays, and over 500 poems. Known for his wit, paradoxes, and rich imagination, Chesterton’s poetry explored themes of faith, morality, beauty, and the human condition, reflecting his deep philosophical and theological convictions. His poetry was characterized by a sense of wonder, a celebration of the ordinary, and a keen understanding of the complexities of life.

Born in London, Chesterton’s literary journey began with a love of art and literature, which he studied at University College London. Although he never completed his degree, his early exposure to the visual arts influenced his poetic imagery, and his keen eye for detail became a hallmark of his work. In 1900, Chesterton published his first poetry collection, “Greybeards at Play,” a humorous and whimsical exploration of human nature that showcased his gift for clever wordplay and satirical commentary.

Chesterton’s poetry often reflected his deep religious beliefs, which became more pronounced after his conversion to Catholicism in 1922. His poem “The Ballad of the White Horse” (1911) is considered one of his masterpieces—a narrative poem that tells the story of King Alfred the Great’s battle against the invading Danes. Combining historical legend with allegory, the poem celebrated the virtues of faith, courage, and perseverance.

Many of Chesterton’s shorter poems, such as “Lepanto,” a rousing tribute to the Christian victory over the Ottoman fleet, and “A Christmas Carol,” which combined festive imagery with spiritual reflection, demonstrated his ability to weave humor, devotion, and historical insight into lyrical verse. His poetry was also marked by a profound appreciation for paradox, evident in works like “The Donkey,” where he transformed a humble, scorned animal into a symbol of divine grace.

Beyond his poetry, Chesterton’s impact on English literature was profound, with his writings influencing figures like C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien. His poetic voice remains celebrated for its clarity, joy, and intellectual depth, offering readers a window into the mind of a thinker who saw the world as a place of endless mystery and divine meaning. Today, G. K. Chesterton is remembered not only as a master of prose but also as a poet who brought wisdom and wonder to every verse he penned.

Elegy in a Country Churchyard

The men that worked for England

They have their graves at home:

And bees and birds of England

About the cross can roam.

But they that fought for England,

Following a falling star,

Alas, alas for England

They have their graves afar.

And they that rule in England,

In stately conclave met,

Alas, alas for England,

They have no graves as yet.

The Song of the Strange Ascetic

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have praised the purple vine,

My slaves should dig the vineyards,

And I would drink the wine.

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And his slaves grow lean and grey,

That he may drink some tepid milk

Exactly twice a day.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have crowned Neaera’s curls,

And filled my life with love affairs,

My house with dancing girls;

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And to lecture rooms is forced,

Where his aunts, who are not married,

Demand to be divorced.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have sent my armies forth,

And dragged behind my chariots

The Chieftains of the North.

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And he drives the dreary quill,

To lend the poor that funny cash

That makes them poorer still.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have piled my pyre on high,

And in a great red whirlwind

Gone roaring to the sky;

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And a richer man than I:

And they put him in an oven,

Just as if he were a pie.

Now who that runs can read it,

The riddle that I write,

Of why this poor old sinner,

Should sin without delight-

But I, I cannot read it

(Although I run and run),

Of them that do not have the faith,

And will not have the fun.

The informational article above was composed in part by administering guided direction to ChatGPT. It was subsequently fact-checked, revised, and edited by the editor. The editor/publisher takes no authorship credit for this work and strongly encourages disclosure when using this or similar tools to create content. Sparks of Calliope prohibits submissions of poetry composed with the assistance of predictive AI.